Main Thread

Remote work and the fallacy of cost-of-living adjustments

29 May 2020 by Giles Van Gruisen

The future of work has arrived. Remote-first distributed teams are here to stay, but along with them comes a whole new set of problems for workers. Corporations see an opportunity to grow profits, but employees have the chance to stand up and fight back.

In the last few weeks, we’ve seen some of most influential technology companies announce their active adoption of remote work, embracing some of the rapid change forced upon them by the Covid-19 pandemic. Specifically, Zuckerberg’s announcement that Facebook employees should expect salary adjustments has fueled debate about how remote workers should be compensated when some employees continue to live in Silicon Valley while others set up their homes in more affordable areas.

As CNBC reports:

The company will begin allowing certain employees to work remotely full time, he said. Those employees will have to notify the company if they move to a different location by Jan. 1, 2021. As a result, those employees may have their compensations adjusted based on their new locations, Zuckerberg said.

Sure, it costs a heck of a lot less to live Wichita, Kansas than it does to live in Silicon Valley. On the surface, this makes sense, but I think it lacks a critical understanding of why engineers are paid highly in the first place, and risks widening the gap between value and compensation that has led to enormous inequality in the United States.

Zuck signalled his own reasoning for the change, while offering a rather dire warning to employees:

“We’ll adjust salary to your location at that point,” said Zuckerberg, citing that this is necessary for taxes and accounting. “There’ll be severe ramifications for people who are not honest about this.”

Such a warning seems uncharacteristic for someone purely concerned only with state payroll taxes and income withholdings for individuals. Given the company’s history of mistreatment of its workers, there’s reason to be skeptical of Mr. Zuckerberg’s claims.

An elite charade

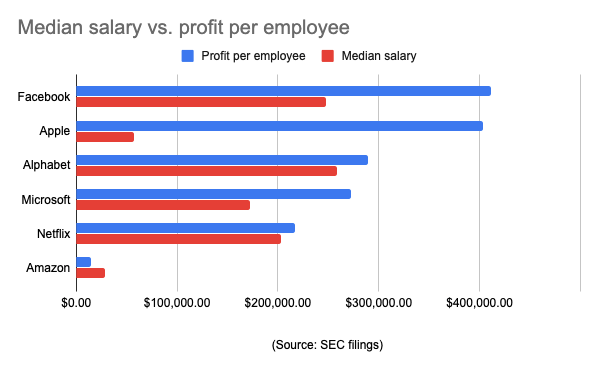

Truthfully, those state-by-state tax and accounting differences are nominal for a company that generated a profit of more than $400k per employee last year:

It should be clear that Zuck’s focus is on maximizing shareholder value. There are numerous strategies for a public company like Facebook to do that, but generally speaking more profit means more value.

(Amazon is a interesting exception, as their fundamental strategy is to reinvest nearly every dollar of profit back into growth, as evidenced by the relatively low profit-per-employee figure in the chart above).

Maximizing profits happens in one of two ways: either by increasing revenue or by decreasing costs. Every role in a profitable business supports one of these two functions, directly or indirectly.

One way to decrease costs, as you may have guessed, is to pay your employees less.

Voodoo economics

Hopefully it’s obvious that Facebook sees the shift to remote work as a way to dramatically reduce the costs of their many thousands of employees and improve their bottom-line.

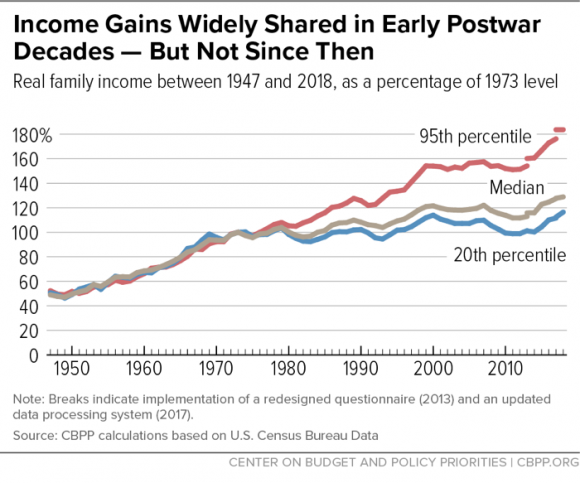

Now, maximizing shareholder value at the expense of employees is nothing new. Indeed, defenders of supply-side economics will say this is by-design: increase profits such that those funds can be reinvested into growth and used to hire additional workers, and workers will benefit in the long-run. This is the basic idea behind trickle-down economics. It sounds alright in theory but, historically, it doesn’t work. Nothing stops executives from pocketing the profits or disbursing them to shareholders, so supply-side economic policy typically just enriches the people at the top.

In the US, we see this in the rising levels of income inequality since 1981, when the Reagan administration implemented massive tax cuts in the hopes of stimulating economic investment:

Equal pay for equal work

So why then are people so upset? It comes down to a very natural feeling of discomfort in seeing people paid differently for doing the same work. Consider the lives of two (hypothetical) Facebook engineers.

At the start of 2020, Carly and Marcus were both working on the same team with the same job title in Silicon Valley. They even started on the same day, got promoted around the same time, and thanks to the power of hypotheticals to prevent gender discrimination, they earn the exact same salary and benefits. When the pandemic struck, Carly moved back to her hometown in the mid-west, and decided to stay when the company announced they would continue to support remote workers after lockdowns were over. Meanwhile, Marcus decided to continue working remotely but remain in San Francisco.

After her move, Carly received a cost-of-living adjustment where her compensation was reduced by 20%, while Marcus’s pay stayed the same. For all intents and purposes, Carly and Marcus each still contribute an equal amount of value to the company, so why should Facebook profit that much more from Carly’s hard work? Why should she be paid less than Marcus for doing the same work?

Carly’s hometown affects her ability to create value for Facebook in the same way that her womanhood does, which is to say: not at all.

People seem to understand this, and they’re right to be concerned. If we want to continue to enjoy the benefits of remote-work, then we ought to be proactive in standing up to protect ourselves from arbitrary discrimination.

Why should we tolerate geographic discrimination any more than we tolerate gender discrimination, when neither has any affect on our value as an employee? In the other direction, why should Marcus earn more because he decides to remain in Silicon Valley? After all, it’s no longer the case that Facebook needs employees to live in one of the most expensive places, so why would they pay a premium?

This raises another question: why are these engineers paid so highly in the first place? I would like to explain why answer is not simply, “because they live in Silicon Valley.” by first sharing a bit of background on how cost of living came to be used to determine wages in the US.

Just Do It

At the beginning of the 20th century, industrial workers’ compensation comprised primarily piece work wages. Pay was dependent on the total unit production of the worker, regardless of the time it takes the worker to produce those units. Put simply, worker compensation was more closely tied to their contribution to the value chain.

This is hardly ideal: if the retail value of units goes up, so does the value of each worker’s labor, but the employer is more likely to take advantage of the opportunity for labor arbitrage, pocketing the difference rather than raising their employees’ pay. On the flip side, you can be sure the employer would share any decrease in sales with workers by reducing their pay or letting them go. Taken to its logical end, a business with poor economics means its employees may struggle to put food on the table. The result is often sweatshop and/or child labor.

It wasn’t until 1931, amid The Great Depression, that the United States established a federal requirement to pay workers a “prevailing wage” for public works projects. Similar policy for the private sector soon followed. Because labor-time was the singular standard unit to which a dollar value could be assigned, an hourly minimum wage was chosen.

Low-skilled workers suddenly had some against abusive employers, and companies with economics which could not sustain the minimum wage were guaranteed failure. Very well.

From ‘piece-wages’ to ‘peace, wages’

An unfortunate side effect, however, is weakened link between value and compensation. By its very nature, the federal minimum wage dictates what is “enough” for a worker to at least take care of themselves. Anything above that becomes a premium to attract and retain workers with specialized skills, rather than a bonus to reward valuable work.

Nowhere is this more apparent than tech, where a lop-sided labor market requires firms to shell out high salaries and benefits for their employees, or risk losing them to the company down the road.

The upside of technology is so great that it justifies large, risky capital investments. This is the basis of venture capital; a few big wins justify many smaller losses. While it’s easy to think that upside justifies high employee compensation, the reality is more nuanced. The upside justifies the demand for tech labor, but the scarcity of that labor is what justifies the price.

If businesses could pay engineers less, they absolutely would; but there aren’t enough of them, so they can’t. It is no coincidence that many tech companies and their founders support code schools and programs that grow the size of the talent pool. This also only goes so far, as compounding abstractions increase engineers’ productivity, and demand for software continues to increase.

As remote work tooling improves, the barriers that previously kept tech workers co-located with their employers are falling, opening up the labor market for employers and further increasing them opportunities for labor arbitrage.

Ever the optimist

Some employers go out of their way to offer their employees profit-sharing bonuses where a percentage of quarterly profit is distributed to each employee, typically based on length of tenure. Unlike traditional incentive programs, profit-sharing builds alignment and trust among employers and employees, and leads to improved productivity and job satisfaction.

Profit-share programs are still entirely optional, though there are some tax incentives. Moreover, any “good will” rationale should be taken with a grain of salt. It is usually another premium in order to attract and retain top talent.

That doesn’t mean it’s a bad thing, however, particularly because it re-introduces the correlation between value and compensation, thereby reducing the opportunity for labor arbitrage. I hesitate to say these programs should be celebrated, but they should be more commonplace.

Naturally, profit-sharing leads to a more even distribution of wealth, spreading out among employees what would otherwise have been concentrated to a few founders or shareholders.

I don’t have all the answers, but I am hopeful for the future.

I don’t expect to convince anyone that they should pay their employees according to their value, but I hope to make clear how remote work risks increasing opportunity for labor arbitrage and how that leads to greater income inequality. I hope that others begin to understand the risk of inaction and see the need to fight for economic policy that reduces discrimination and wealth inequality.

We cannot rely on the good will of a few capitalists to deliver widespread economic prosperity for the rest of us.

Thanks for reading. I plan to follow up on how more equitable compensation for remote workers can lead to a broader redistribution of wealth and provide benefits that extend beyond tech. Subscribe below to be notified when that gets published.

Main Thread is a newsletter and blog, loosely focused on software and technology, written by Giles Van Gruisen.

© 2020 Giles Van Gruisen